A philosopher and a photographer share knowledge.

Here is the talk!

Claire Anscomb, Philosopher discusses with Almudena Romero, Visual Artist

Almudena Romero’s diverse works represent a vast exploration of the social and physical possibilities afforded by analogue photographic methods and processes. She has used chemical processes, such as the wet-plate collodion process for the series Performing Identities to explore issues of national identity from a decolonial perspective, and organic processes, such as chlorophyll printing for Growing Concerns to examine the legacy of the plant trade, colonialism and migration. These processes and topics raise a number of questions that are the subjects of live philosophical debates. In this interview, Romero offers her perspective on some of the key points of contention amongst philosophers – about what photography is, how the medium can contribute to artistic and epistemic practices, and how we relate to the depicted subjects of photographs.

CA: Your latest series, The Pigment Change, sees you exploring photography in relation to other art forms including video, performance and installation. One of the big debates amongst analytic philosophers of art is where the boundaries of photography lie – what do you think photography is and what a photograph is?

AR: I understand photography from an etymological perspective – so, “photos” + “graphos” = “light writing”. I think of photography as a process, not as a result, and therefore going sunbathing and recording your swimsuit outline, that’s a photographic performance – and that is the moment you use that[process] to explore the meaning of something or a concept that you want to bring your perspective on. Then, it’s a tool for self-expression, for artistic reflection. Photography has been used and kind of overused for documentation purposes, and the perspective on photography as a means to express views, like any other art form, has been historically neglected. I like using photography as a tool for self-expression – in The Pigment Change to express my views on production, reproduction and the role of an artist in an environmental crisis. To do that it is easier for me to combine it with other artistic forms and document the photographic process I want to use in the form of video but also creating sculptural works via resins. So, this thing of photography intertwining with other art forms is a discussion that we only have in photography. If we were talking about sculpture or painting it would be so obvious that it intertwines in many cases. In the same way that sculpture went off the plinth many years ago, photography should be going out of the frame and many contemporary practitioners are embracing this perspective – I guess my practice sits on that view.

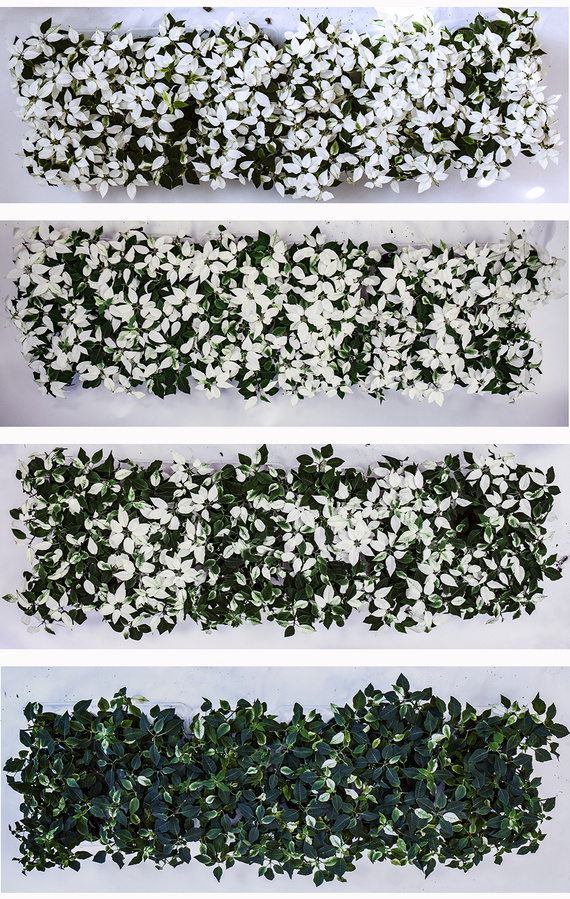

CA: Picking up on the theme of intertwining art forms, I was interested to see you describe both the performative process and the physical output as photographic pieces for the work Spring, which sees you creating an artificial spring in your studio to change the pigment of the leaves of fifty poinsettias. When it’s still relatively new for previously separate artforms to come together, some philosophers might want to label these combinations ‘hybrid arts’. Is that something that you are resistant to – do you see that what you are doing is just another way of practicing photography, or is it important that we should see these works as combining artforms in a new way?

AR: The way people brand you, I think is more related to the people, than to your work. I see myself as an artist working with photography and I don’t see myself as a gardener, or as a bio-artist. The thing is that I understand photography happens in many forms and materials, and the moment you engage with photography as a process that can exist in many places and can take many forms, then you start seeing photography everywhere. In Spring that is what is happening. In Spring and Autumn, both parts of the Pigment photo series, it’s just a plant changing pigments. In scientific terms, that process is called “photoperiodism[?]” so it’s clear that there is a photographic component. It’s due to changing the wavelength that plants change pigments. Now, is that a form of artistic expression? Well, for my project it is because what I am doing is forcing the plant to do that pigment, to talk about photography as something that can manifest in nature.

CA: Photography has frequently been used for documentary as well as artistic purposes. Your series Performing Identities explores the legacy of understanding photography as a “truthful” or “objective” medium. Are there any respects in which you think photography is objective or truthful, and if so, how we could use photography, in your broader sense to be truthful or objective?

AR: We have this understanding that objectivity as such exists, or could exist, and I think that relates to our culture. In terms of using photography for that purpose, back in the 19th century, it was obviously very much linked to rationalism and this period of the 19th century. But, the script that went behind that was the surveyance of people, differentiation, exclusion. So, there was a wider agenda supporting all that and benefitting from that, and we still have that legacy with us, part of it because we still really relate identification with identity. For instance, at least in Spain, we have something called “ID cards”, which doesn’t mean “identification card”, it means “identity”- as if it would really link to the person that you are and it’s difficult to break that distinction that the West created. Back then, […] your outer appearance and outer persona sort of reflect on your inner self and photography has enormously contributed to that understanding of the self and the medium. These days, […] photography is a purveyor of truth and has also been kind of liberated from that task thanks to digital photography because if you want to provide evidence, three snaps and it’s done. It has also been questioned thanks to digital means too, like all the Instagram filters and how easily everything can be edited. I think we’re all much more aware now that photographic evidence, it’s very relative and I think, luckily and thanks to digital means no one will argue that a photograph is now a provider of truth and objectivity. I think even my 11-year-old niece is very aware that’s a fallacy and photography represents your views and yourself

CA: On the subject of self-expression – your works are often quite collaborative and incorporate some form of knowledge-exchange. Participants in Performing Identities, for example, learnt how to produce a tintype photograph. Do you think, given the proliferation of visual media in today’s society, that it is important for us to learn about more about different ways to use visual media and theopportunities or limitations that come with these?

AR: I think it’s very important to learn different ways of producing images in the same way that when we are learning at school about reading and writing, we are shown poetry, theatre, many ways of artistic expression that can happen by written means, and that enriches our perspectives on what can we do when we are writing. I think it is important to open conversations about what photography is and what it can be. Also, it makes it more accessible to everyone. To me, when I was doing the Performing Identities series, there were several things that were collaborative. One is that [the participants] needed to self-identify as immigrants and come to the studio, and that was very important because 19th century photography, and especially the wet collodion process, which I was doing the tintypes with, was one used to sustain a discourse of differentiation – “that’s the people in the colonies and this is us”. So, the idea was to use exactly the same process, but instead of reinforcing exclusion and differentiation, to use it in a much more inclusive manner, so people who will self-identify as immigrants – the way I self-identify myself too – were welcome to come to the studio and have a tintype made. They will keep a copy, I will keep the other, so the archive is shared as well, which is a dynamic that I like because it doesn’t necessarily favour capitalist exploitation of photography. When people ask me:“So where is the archive?” Well, the archive is in two-hundred houses and mine. So, it’s uncontrollable and not subject to that sort of exploitation of limited editions that can be commercialised, owned, resold etc. […] Normally migration and photography has such a bad relationship, like there are so many photographs, someone taking a picture saying “this is an immigrant” – the way they are depicted…it is a threat, or usually with pity, or sorrow, and I didn’t want to link to any of that[…] I put an open call for people who will self-identify as immigrants […] so, it was like a positive thing if you self-identify like that and you want to take the time and energy to come to my studio then I am more than happy to share with you the wet collodion process and give you a tintype. And we’re going to have a positive, joyful thing to do, while we are talking about migration and photography. So, the entire point was to change the dynamic from the beginning to the end, from the production to the way it is consumed, to the way it is presented.

CA: As we discussed earlier, we tend to mostly interact with photographs via electronic screens, I think it’s really interesting to bring back physicality and tactility to the process – do you think that it is important to relate to photographs as physical objects?

AR: Yeah, to me the physicality of photography is something very important, because I think of it as a process, not as a result. The places and the forms where that process manifests are interesting to me. And I think also, in younger generations, there is an interest as well in physical things. I see it in my courses when I teach – many people are interested in producing physical objects and having physical things maybe in their houses. The photographs they produce, once they have the objecthood form, once they are printed and exist in a tactile manner, they seem to acquire a certain value for people, much higher than we used to have. […] For instance, going back to my niece, the four or five pictures she has printed, they are super important, they are properly framed, placed in an important place in her bedroom. She doesn’t have photo albums like I had when I was teenager, but the four or five objects that have gone through that selection are very, very meaningful to her.

CA: It’s commonplace in photographic theory to talk about photographs as helping us to sustain a sense of contact with their subjects. For instance, in Performing Identities, even though the tintype photographs aren’t as sharp as contemporary digital photographs, there is that sense that you’re “really seeing” that person. Is that something that you consider when you’re making these works, and if so, whether you think that makes photography quite powerful tool for galvanising social action?

AR: Well, in terms of appearance, the wet collodion process is not sensitive to all of the visible light and it is sensitive to UV light – this is a light that we do not see, so people actually look very different from what they look in real life than in their photographs. I teach this process very regularly…it always happens in the workshops that people are like: “Oh wow, I look like a completely different person”. Because it’s sensitive to different lights than the ones that we see, it changes the appearance of the person in the picture. But I think one thing that I like about the wet collodion process in the Performing Identities, is that it also made it obvious that photography is sometimes more self-referring than referring to the subject and that is important when talking about immigrants and migration. The way migration is depicted says a lot about the way we understand migration. But, in the case of photo albums and family albums, I think much of the reason we have pictures is so we tell younger generations, “This was aunty Lily and Grandad…” – so you know who is who. […] So, that is truly a documenting use of photography, but also, it’s linked to the idea of legacy – photography has also been charged with that difficult task.

CA: Relatedly, your work Family Album, where you expose negatives from your family archive onto cress,reflects this sense that photographs can be quite generative, even though we maybe think of them in a way as being quite static. Is that something that you’re thinking about with your more organic processes?

AR: Well, yeah, it’s photographs that eventually grow and disappear just as we do. So, I wanted to revisit this idea of the family album and The Pigment Change is all very much linked to conversations I have had with my mum, because we locked down together and so we had a lot of conversations. But also, because the project talks about maternity. What I see with my mum and with the photo albums is that for her, it’s important, the “who”: who was this person and who will be the continuation of the family? To me, when I think legacy, it’s more the “what”. What are we leaving?And expanding the understanding of photography and researching more sustainable photographic materials relates to that. It’s not only intelligent for me as an artist to find forms of expression or using photography that I’m going to be able to access in thirty years, its also beyond that… what’s the legacy, rather than who is receiving it, it’s something that is very personal to me. And so, I wanted to use photography to explore that other perspective, much more linked to the “what” than to the “who” and who is depicted. I wanted it to be a living thing, but also making it in a way, that it decays and dies in four or five days, so making the process of disappearing, as we do, very obvious.

CA:Is the sustainability of photography what you’re currently working on?

AR: Yeah, at the moment, and the more I produce about it, the more I am engaging from this perspective that, because, I am an expert in nineteenth-century photographic techniques, and I have worked with the wet collodion process, and I know perfectly well in a few year’s time, much of the chemicals that it uses are going to be restricted and that is good for practitioners and good for the environment and good for everyone […] And so, researching materials that artists we can have access in the future, it’s an entirely survivalist strategy as an artist. But I’ve also been thinking “what’s the point of producing if you’re just only adding and contributing to the accumulation problem?” I think research on sustainability cannot only focus on the materials, it also needs to wonder: “why are you producing at all?” Because we have enough and so how is this contributing to the conversation, or how is this expanding the conversation on what photography is, what photography can be, artistic expressions and the conversations that we are having today. How does this contribute or facilitate new conversations on photography because otherwise, if it’s just about adding and accumulating, then it’s being part of the problem rather than any possible solution.

Claire Anscomb

Philosopher

Claire Anscomb received her PhD (2019) in History and Philosophy of Art from the University of Kent, where she is an associate member of the Aesthetics Research Centre. Her research interests include hybrid art, the epistemic and aesthetic value of photography, and creativity in artistic and scientific practices. Her work has been published in venues including the British Journal of Aesthetics, the European Journal for Philosophy of Science, and the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. She was awarded the 2021 John Fisher Memorial Prize from the American Society of Aesthetics and she is the recipient of the 2021-22 British Society of Aesthetics Postdoctoral Award for a project that she will commence on AI and image-making with the Philosophy Department at the University of Liverpool. She is co-editor of the peer-reviewed journal, Debates in Aesthetics and also a practicing artist. Her practice is centred around drawing, which she uses to explore themes surrounding visibility, including practices of recording and documenting the world, and making the invisible visible, from genetic disorders to sound. Her work has been exhibited in venues including the Jerwood Space, London, and Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. She has been the recipient of awards for her work including the Anthony J Lester Young Artist Award (2019), the Arts Club Charitable Trust [now Contemporary Art Trust] Award (2015), and the Signature Art Prize, Drawing and Printmaking (2014).

Almudena Romero

Visual Artist

Almudena Romero (b. in Madrid in 1986) is a visual artist based in London working with a wide range of photographic processes. Her practice uses photographic processes to reflect on issues relating to identity, representation and ideology. Romero’s works focus on how perception affects existence and how photography contributes to organising perception.

Romero’s practise has been exhibited at international public institutions including the Victoria and Albert Museum (UK), National Portrait Gallery (UK), TATE Modern-TATE Exchange (UK), The Photographers’ Gallery (UK), Tsinghua Art Museum (CH), Le Cent-Quatre Paris (FR), University of the Arts London(UK) and international photography festivals such as Unseen Amsterdam (NL), Les Rencontres d’Arles (FR), Paris Photo (Upcoming)(FR), PhotoLondon (Upcoming)(UK), Circulations (FR), Belfast Photo Festival (UK) and Brighton Photo Biennale (UK). She has received various awards and bursaries including the Heritage Lottery Fund, Creative Europe Fund, Arts Council England (2018, 2020,2021), London Community Foundation (2019), a-n Bursaries (2019, 2018), and awards from private foundations including the Richard and Siobhán Coward Foundation, The Harnisch Foundation and BMW France Culture. Romero has also been awarded prestigious international residencies at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute(China) , Penumbra Foundation (USA), ISCP New York( USA), BMW -Gobelins (France), Lucy Art Residency (Greece), Whitechapel Gallery(UK) and National Portrait Gallery (UK), and has been nominated for the Prix Pictet (2021).

Romero has received public artwork commissions from Team London Bridge, Southwark Council, Emergency Exit Artist, Wellcome Trust and Bow Arts Trust for the London Festival of Architecture. Her practice has been published in monographs by the Photography Archive and Research Centre at University of The Arts London and by XYZ Books (upcoming) and featured in BBC Four, BBC Two, FOAM Magazine, Photomonitor, Radio France Internationale, TimeOut, Fisheye magazine, DUST magazine, EXTRA magazine (FOMU, Foto Museum) and other international media.

Romero holds an MA in Photography from the University of the Arts London and a Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice in Art, Design and Communication (university teaching qualifications). She is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. In 2020, Romero worked as a professor of photography on Stanford University’s Bring Overseas Study Program in Florence, Italy. Romero has also delivered courses, lectures and artist talks at universities and museums internationally including Falmouth University (UK), University for the Creative Arts (UK), University of Westminster (UK), Camberwell College of Arts (UK), London College of Communication (UK), Kingston School of Art (UK), Southampton Solent University (UK), Chelsea College of Arts (UK), University College London (UK), School of Visual Arts New York (NY), GOBELINS. Ecole de l’image (FR), IESA (FR), Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (CH), Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum (JP), Sotheby’s Institute of Art (UK), Royal Society of Chemistry (UK), Royal Society (UK), Estorick Collection (UK), Wellcome Trust (UK) Victoria and Albert Museum (UK), Science Museum (UK), National Portrait Gallery (UK), South London Gallery (UK), Whitechapel Gallery (UK), The Photographers’ Gallery (UK), TATE Modern (UK), TATE Britain (UK), and Fundacion Mapfre Cultura (Spain).